As the world’s most densely populated continent and fastest growing economic region, Asia is often considered as football’s rising superpower. But until now, Asia has regularly underperformed on the international stage. Only six times have Asian countries reached the sudden-death stages of the World Cup, and of those, South Korea and Japan were successful in 2002, when they co-hosted the competition.

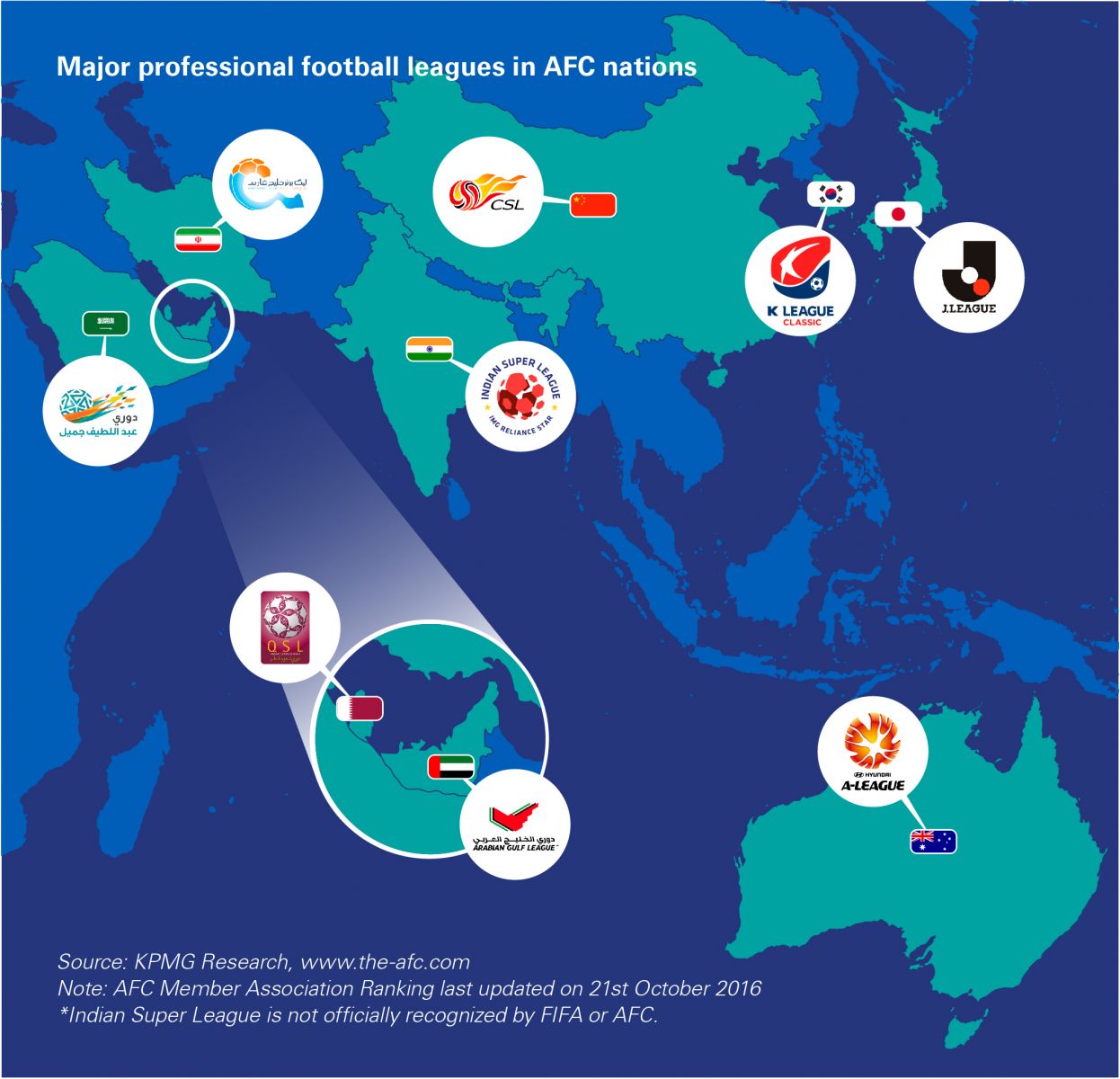

For many years the lack of developed economies and competition with other major sports in the region has stymied the development of successful youth development programmes and professional leagues. However, in recent times, Asian Football Confederation (AFC) nations have made major efforts to narrow the gap with their Western counterparts. In this article, KPMG’s Football Benchmark team reviews the state of Asia’s major leagues.

EAST ASIA

The recent football revolution in China has not only resulted in massive investment in European clubs but has also been the catalyst for renewed stakeholder confidence in local competition. Earlier this year, the Chinese Super League (CSL) sold its domestic broadcasting rights for RMB 8bn in a five-year agreement (EUR 213m per season), the largest of its kind among Asian leagues. While the league has yet to develop a sustainable business model, the investment in foreign players and the growing interest of local fans – average attendances in the 2016 season have surpassed the 24,000 milestone - have already consolidated the CSL as Asia’s top league in terms of average attendances and squad market value (EUR 20.4m[1]).

The rise of China has, to some extent, relegated the Japanese J. League to a second plane. However, the J. League continues to evolve, as evidenced by the inauguration in 2013 of a third-tier for its professional football structure, and remains a benchmark for Asian competitions in terms of professionalism and long-term planning.

As a result of young Japanese talent moving to Europe and a relatively low level of investment to attract international players and coaches, attendances have decreased in the last decade, stagnating below 18,000 per match, and the average squad value (EUR 12.7m) is already far below the top division in China. However, the J. League is also set to benefit from a new broadcasting contract. Japanese football’s established community links and the resilience of the local market have both been instrumental in driving a reported JPY 210bn 10-year broadcasting deal (EUR 183m per season) with London-based Perform Group, which would increase fourfold the value of the current agreement.

Internationally, at both national and club level, Japan has faced tough competition from their South Korean neighbours. Indeed, South Korea is the only Asian nation to have reached a World Cup semi-final and its clubs hold the best record in the AFC Champions League (10 titles). Despite international success and the relatively healthy average market value of its squads (EUR 9.8m), the K-League Classic, South Korea’s domestic top-division, has struggled to generate significant interest among domestic broadcasters and spectators.

CENTRAL AND WESTERN ASIA

Thanks to local investment, the squads of the Qatar Stars League and the United Arab Emirates League have a very similar average market value (EUR 9.4m and EUR 9.1m respectively) and have regularly achieved qualification to the latter stages of the AFC Champions league in recent seasons. That said, the small populations of both Qatar (2.2 million) and the UAE (9.2million) present a challenge for the long-term sustainability of both leagues.

While lacking the modern and diversified economies that support both the Japanese and South Korean competitions, some Central and Western Asian leagues are underpinned by a strong football culture and very passionate supporters. Although average league attendances are usually below the 10,000 mark, impressive crowds have been recorded for local derbies, such as the games between Saudi’s Al Ahli and Al-Ittihad (above 60,000) and Iran’s Persepolis FC versus Esteghlal FC (100,000).

The Saudi professional league is in the process of privatizing its clubs (average squad market value EUR 5.7million), and in 2014 signed a 10-year deal with the Dubai-based MBC group which reportedly values the competition’s broadcasting rights at SAR 410m per season i.e. almost EUR100m. With a slightly higher average squad value and a large pool of potential fans (population 79.1 million[2]), the Persian Gulf Pro League (average squad market value EUR 6.5m) also has the potential to attract significant revenues, currently hampered by the lack of a competitive broadcasting market.

CLOSED LEAGUE MODELS

In Asia, football very often competes regionally with other sports such as rugby and cricket. In these cases, closed leagues have proven to be an alternative for investors willing to professionalize the sports in territories such as Australia (joined AFC in 2006) and India.

Using a closed league model, the Australian A-League has just entered its 12th season and continues to grow, as it expects to significantly increase the value of its reported AUD 40 million per season (EUR 28m) which expires next year. Also competing against the massive popularity of cricket in the local market, the Indian Super League (ISL) has also opted for a closed model. In this case, the league’s broadcaster, one of the organisers of the ISL, has played a key role in maximising the media reach of a competition which in its 2015 edition reached average attendances above 26,000, higher than both Serie A and Ligue 1. Although this short-term tournament is not yet recognized by the AFC, the All Indian Football Federation (AIFF) has already revealed a draft to integrate the competition in the domestic structure of Indian football.

While the operating landscape for the various European leagues is broadly similar, the environment in Asia is very diverse. Against a backdrop that includes developing economies, economic volatility and additional competition from European leagues and other sports, the challenges are manifold for clubs, leagues and investors. Moreover, as a result of the limitations on the number of foreign players that clubs can field, the ability to develop domestic talent will be a determinant factor in the long-term success of these young competitions; which still need to find sustainable models to maintain and increase the current level of interest.

The Asian continent has demonstrated its hunger for top quality football, the question is now when and which of its leagues will be able to compete and eventually challenge the game’s traditional superpowers in the long term.

Further investigation into this and related topics, as well as analysis of industry data, can be undertaken for you by KPMG Sports Advisory Practice. Our subject matter experts can also assist stakeholders in assessing and interpreting the potential impact on their organizations of any particular piece of research, identifying the underlying reasons behind specific trends or developing potential solutions and considering future scenarios.

[1] Average squad market value data retrieved from www.transfermarkt.com

[2] Population figures retrieved from www.worldbank.org