It is the first time in football history that one country is sending all four teams to the finals of the top two European club competitions. Crystallization, defined by the virtuous cycle of economic power and sporting performance, is palpable on all fronts, if we look at the dominance of the top six Premier League clubs, or the supremacy of the big five leagues in the European tournaments. However, the last stages of the tournaments proved that beyond the fundamental role of big money, other aspects, such as prudent strategic squad development, along with passion, hunger for success and determination can also make a difference and can create awe-inspiring memories for all football lovers.

UEFA Champions League (UCL) final

The last stages of this year’s Champions League offered the best football can offer. Ajax’s amazing run, eliminating the likes of Real Madrid and Juventus, as well as Tottenham’s incredible comeback denying Ajax from progressing to the final, or Liverpool beating Barcelona in the semifinal, overturning a 0-3 deficit – some performances that will go down in football history.

This year’s final demonstrates the obvious dominance of the English Premier League. Interestingly, it will be the third all-English final in the history of the European Cup/Champions League.

Liverpool’s overall international performance has been spectacular, having collected 11 major trophies altogether, including five European Champions’ Cup/Champions League titles. Tottenham boast a more modest record – three shields altogether, including two European League trophies. This is the first time they may grab the UCL title.

However, the two finalists share some similar qualities. Both clubs feature among the top 10 European clubs by enterprise value, demonstrating sustainable operations, and they have seen spectacular development on the pitch in the past several years under their charismatic managers, Jürgen Klopp and Mauricio Pochettino. Both managers have turned their clubs into regular top-four teams during their time in charge, and are famous for their focus on man management.

While some top clubs would spend exaggerated amounts on elite players, developing young talents along with signing players with true vision and planning may help compose a more sustainable and successful squad in the longer run. Liverpool and Tottenham can attribute their success to a high extent to their strategic squad management, which is also true for Ajax, but all employing a different strategy to maximize their squad value within their financial capabilities.

Since the managers took charge, Pochettino (since 2014) has spent altogether EUR 325 million on new players, while Liverpool’s Klopp has dispensed EUR 561 million since 2015. (Barcelona, in contrast has spent EUR 837 million, while Ajax has only spent EUR 139 million in the past five years.)

Liverpool can boast the spectacular progress of some young players, such as Robertson, who joined them two years ago at the age of 23, and the 20-year-old home-grown Alexander-Arnold, but has also been involved in some clever player trading deals, for example, buying Van Dijk and Allison for the price of Coutinho, symbolizing a sensible approach for longer-term team development.

Pochettino is known for his preference for rather improving his squad than amassing them. The fact that Spurs have not signed a player since the 2018 winter transfer window, however, had more to do with the intense effort made in constructing the New White Hart Lane. Interestingly, the last player they bought was Lucas Moura, whose hat-trick knocked out Ajax in the semis. Although Tottenham have spent less money than their rivals in the past five years, Pochettino hinted in the past days, that he would need “different tools to work”, if similar levels of success is expected from Spurs in the future.

Prudent spending based on longer-term planning may also lead to a healthier balance between revenues and squad payments. The staff costs-to-revenues ratio at these clubs in 2017/18 is also rather telling: only 39% at Tottenham, 58% at Liverpool, 57% at Ajax, while 81% at Barcelona, whereas the UEFA Financial Fair Play recommends a 70% threshold.

Ajax has showcased the success of another strategy on talent management. Having a very different budget than the elite clubs, they rely mostly on their long-famed football academy infrastructure, which has been nurturing great talents and on scouting young talents from their domestic league – see more on that here.

Champions League – glory and big money

All teams in Europe dream of playing in the Champions League, both for the fame and for the promise of huge amounts of cash; indeed, the money on offer in the continent’s top club competition is mind- blowing, as it also distributes around four times more money than in the Europa League.

The chart below gives an indication of the difference in UEFA prize money in the two tournaments. Prize money is divided into fixed payments, based on participation and results, as well as variable amounts, which depend on the value of the clubs’ respective TV markets and their historical achievements. Here we showcase only the fixed amounts for maximum sporting performance.

Consequently, major league clubs and top teams from smaller leagues focus on the UCL, and the Champions League has increasingly been dominated by clubs from the big five European divisions. However, that big five league dominance and crystallization in the UCL also give more chances for non-big five league clubs in the Europa League. Indeed, the proportion of non-big five league clubs is significantly higher in the last stages of the Europa League. They sent almost half of the clubs to the last 16 in the past five seasons, and had one club in the semifinals in each season (Salzburg, Ajax, Shakhtar Donetsk, Dnipro and Benfica). Dnipro, Benfica and Ajax also made it to the finals, with the Dutch side only to lose 0-2 to Manchester United in 2016/17.

Europe League final – a springboard for the elite, fame and money for the rest

Both Chelsea and Arsenal qualified directly for the Europa League group stage by finishing 5th and 6th, respectively, in the Premier League in the past season; from their perspective, it is more accurate to say that they failed to qualify for the far more lucrative Champions League. Despite less appeal and remuneration, winning the UEL means automatic entry into the UCL group stages in the next season.

This is exactly the case now – Arsenal have just finished 5th in the Premier League, missing out on direct qualification to next year’s UCL; consequently, they will do their utmost to win the UEL. Chelsea, in contrast, already sealed their next year’s UCL spot by finishing 3rd in the EPL, reducing their motivation more to the glory of the UEL trophy.

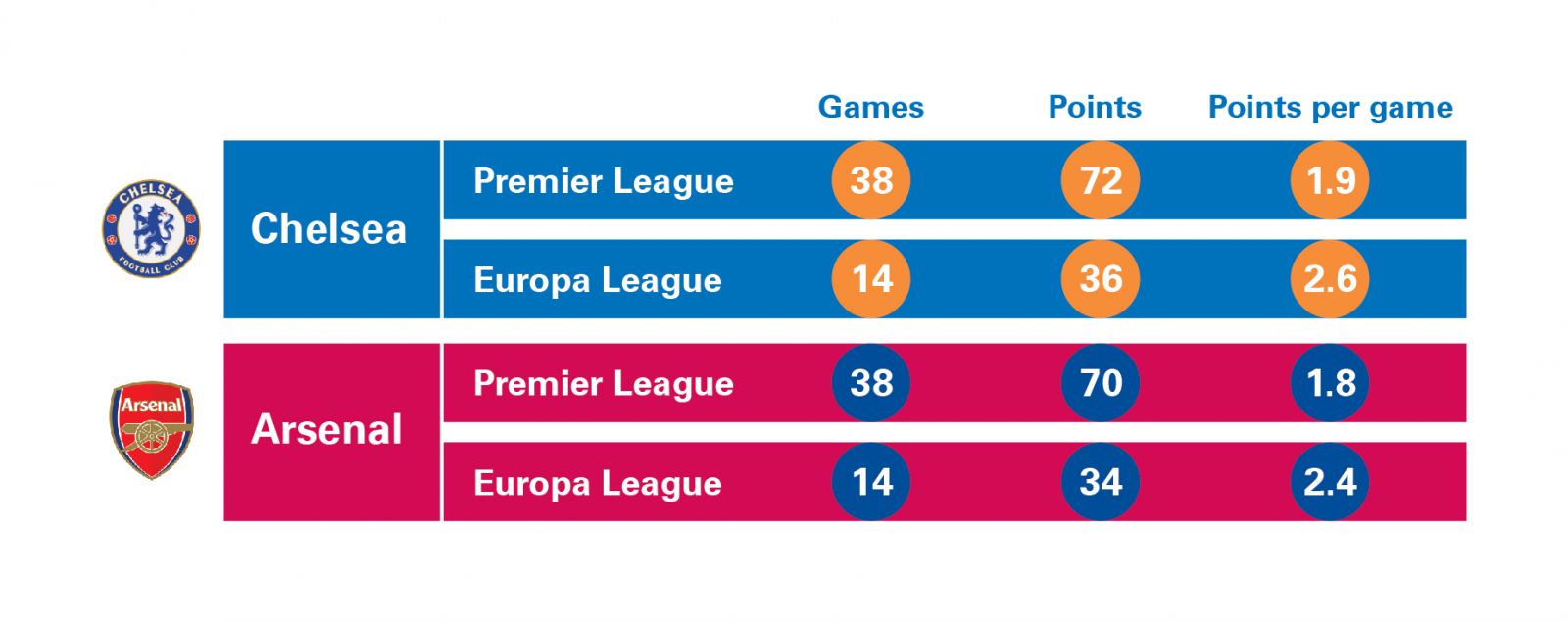

While winning the UEL is obviously a great sporting achievement in and of itself, on the other side, it may be an easier task than finishing in the top four of the very competitive Premier League. The latter requires stable performance throughout the whole season, playing altogether 38 matches, 10 of them against other top six clubs. In contrast, both Arsenal and Chelsea may win the UEL through playing not only fewer games (15 in total), but less competitive ones too – in the knockout phase, Chelsea had to pass Bate Borisov, Rennes, Napoli and Valencia, while Arsenal had to beat Malmö, Dinamo Kyiv, Sparta Praha and Eintracht Frankfurt. The chart below shows that both Arsenal and Chelsea performed better throughout their Europa League campaign than in the EPL this year.

The above logic may be relevant only for the most competitive domestic championships, the English Premier League and the Spanish La Liga: if it is difficult or unlikely to grab a UCL spot in your domestic league, try to win the EL, and thus qualify for the UCL next year. The true reward of winning the Europa League was securing a place in the Champions League in the following season for Sevilla in 2014/15 and 2015/16, and also for Manchester United in the 2016/17. Interestingly, since the rebranding of the EL in 2009/10 season, the winners of the tournament have only been English (Chelsea and Manchester United) and Spanish teams (Sevilla and Atletico Madrid three times each), with the only exception being Porto in the 2010/11 season.

While winning the Europa League title may be sometimes more of a springboard for a few clubs from the most competitive championships, for the majority of leagues and clubs it still remains a source of international fame, and of significant income from the UEFA prize money.