In a previous article, we introduced the different football club owner archetypes, from local businessmen or supporter groups to foreign tycoons or private equity firms, and the key motives that drive them. This time, we focus on foreign investors, especially on those for whom business aspects are important drivers.

While achieving financial gains may seem to be the prime goal for any investment, that is not necessarily always true. Looking at recent foreign ventures in football, we see several high-profile deals where other, strategic aspects appear to dominate. Countries, companies or individuals can improve their brand awareness or public image through acquiring a football club: Paris Saint-Germain and Manchester City are often seen as ambassadors for their owners’ countries, Qatar and the UAE, respectively, while Silvio Berlusconi’s almost 30-year ownership of AC Milan is seen by many as a tool for improving his personal image and foster his political goals. The remarkable Chinese investments into European football can primarily be driven by the geopolitical motivation to attain more advantageous political and business positioning for their fast-growing economy.

Yet, for foreign investors who see European football as a promising vehicle to exploit revenue-generation potential, a look back at some trends, both past and more recent, offers encouragement and can enhance the appeal of football for big money deals.

The first milestone, between the late 1980s and the early ‘90s, was the transformation of football clubs from non-profit to profit-making enterprises, which allowed owners to distribute dividends for the first time. In the mid-90s, with a boom in pay TV subscriptions, clubs were able to register record revenues that could have hardly been achieved with the previous business model, mainly based on gate receipts. In the same period, specifically in 1995, the so-called “Bosman ruling” upended the entire transfer system, as players whose contracts expired were declared free to sign with any club without any compensation to be paid for their services. Furthermore, at the beginning of the 2000s, while TV deals continued reaching new heights, clubs started to develop new, global commercial strategies and thus gained the ability to reach unprecedented worldwide audiences.

More recently, another milestone that has made football more attractive to investors was the introduction of UEFA’s Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations, designed to help boost the economic sustainability of football clubs incrementally, in the 2011/12 season. FFP set a budgetary framework in order to prevent clubs spending more than what they earn and to sanction those who exceed spending over several seasons. Indeed, in the 2011/12 season, altogether the 700 main European football clubs registered cumulative losses of EUR 1.7 billion, while, after the introduction of FFP, those losses started to decrease and by the 2017/18 season had been turned into a profit of EUR 579 million. In the past season, the aggregate profit has somewhat decreased, but the result was still positive.

Last May, the KPMG Football Benchmark’s latest Club Valuation Report revealed that the football industry was evolving at an exceptionally fast pace: for the second consecutive year, the overall enterprise value of the 32 most prominent European football clubs increased by 9%, while the STOXX Europe 50 Index (which is Europe’s leading blue chip index, providing a representation of super sector leaders in Europe covering 50 stocks from 17 European countries) showed a year-on-year decrease of 13%. All in all, according to UEFA, the European football market grew from EUR 13 billion in 2010 to EUR 21 billion in 2018 in operating revenues, which is equivalent to 65% growth.

Nowadays, football is increasingly perceived as an optimal channel to diversify ownership portfolios, to promote a brand by being associated with big-name sponsors and stakeholders and to build and position a brand to win new markets and customers, even globally. In addition, Europe is seen as a huge and lucrative market, especially for brands established in China or the USA, that are connected to sport and want to enter into European markets. Last but not least, a football club itself can be a lucrative business, if on-pitch success is combined with strategic and efficient management.

Obviously, the big five European football leagues present the most attractive markets for potential investors. However, the differences in their levels of appeal are significant.

The German Bundesliga is not a real option for investors who want control over an acquired club, because of a 50+1 rule designed to ensure that the club's members retain overall control by owning 50% of shares, +1 share, protecting clubs from the influence of external investors.

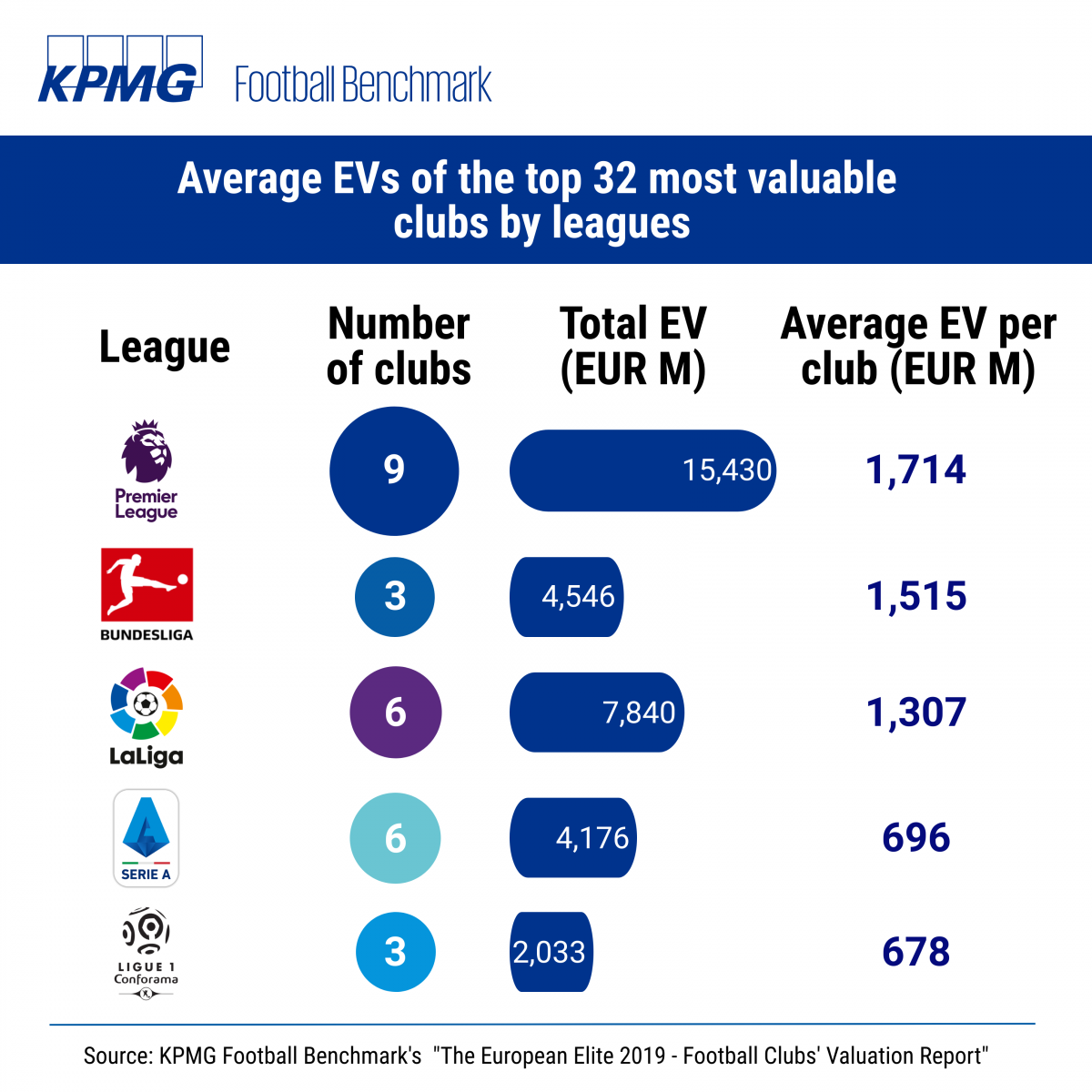

The prominence of the English Premier League (EPL) can be inviting, while English clubs overall are rather expensive. According to KPMG Football Benchmark’s latest Club Valuation Report, the average enterprise value of the English clubs among the 32 most valuable European clubs is well above that of the Spanish, French or Italian top clubs. The big deals of Manchester United, Manchester City and Arsenal were all beyond half a billion GBP, while the GBP 300M price tag on Liverpool in 2010 or the GBP 140M Abramovich paid for Chelsea in 2003 may seem to be a bargain today. Latest media reports reveal advanced talks on the potential takeover of Newcastle United FC by a group of investors led by Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF), with the deal valuing the club at GBP 340M.

It is also telling that Britain's richest man, Sir Jim Ratcliffe, who has been linked with a bid to buy Chelsea, said recently that he has no plans to invest in an EPL team as the valuations of top-flight English clubs are, as he put it, "a bit silly". In contrast, his chemicals firm INEOS bought French Ligue 1 side Nice last August and Swiss second division outfit Lausanne in 2017.

In addition, EPL is probably the most competitive domestic championship, where disrupting the dominance of the traditional big six clubs — and thus reaching a place that rewards an international tournament entry — is a very tough challenge. Nevertheless, the recent performances of Leicester City (where a 60% majority stake was bought by the late Thai businessman Vichai Srivaddhanaprabha's in 2010 for only GBP 39M), or by Wolverhampton Wanderers (purchased by Chinese investment firm Fosun International in 2016 for GBP 45M), can serve as inspiration for investors who are brave enough to take on the seemingly impossible.

Quite similarly, the Spanish LaLiga is highly competitive: in the past five seasons the dominance of Barcelona, Real Madrid, Atletico Madrid and Valencia on the top four posts was challenged only by Villarreal and Sevilla, once each. Clubs are expensive too. Nevertheless, the Spanish market has recently been busier than ever, with even some second division clubs having changed owners. Thanks also to an internal FFP regulation applied in recent years, Spanish clubs have become more sustainable and profitable, enhancing their attraction to foreign investors. The biggest deal in recent years was the Chinese Rastar Group buying Espanyol for EUR 150M in 2015 (a club that today is struggling on the field). Other notable investments included the Chinese Wanda Group buying 20% of Atletico Madrid for EUR 45M (with shares already sold on to Israeli Quantum Pacific) and Singapore magnate Peter Lim purchasing 70% of Valencia for EUR 94M. Granada was bought in 2016 by the Chinese Link International Sports Limited for EUR 37M, while former Brazilian superstar Ronaldo acquired a majority stake in Real Valladolid.

The French Ligue 1 seems to be increasingly attractive for foreign investors, as the league is less competitive: the past five seasons were dominated by PSG, Monaco and Lyon at the top three spots (with direct access to UCL), with Lille, Nice, Saint Etienne and Marseille also gaining access regularly to EU competitions. Ligue 1 also has the least expensive clubs among the top five leagues: even PSG cost only EUR 100M for their Qatari owners in 2011/12. The past several years saw over 15 foreign majority buy-ins, most of them in the range of EUR 10-20M. Nevertheless, most recent deals — the purchase of 20% of Lyon by Chinese IDG Capital Partners, Nice by British energy group INEOS and Bordeaux by General American Capital Partners – all for around a reported EUR 100M – indicates that top division French clubs do present opportunities for foreign investors.

Despite the overall lackluster performance of Italian football in the past several years, clubs in Italy’s Serie A probably bear even more potential for investors. The country has one of the richest and most prestigious football histories and cultures: an abundance of trophies both at the national and club level, legendary players, top coaches and famous clubs — all great assets when branding is a key factor in a potential deal. Italians clubs are also less expensive by comparison: among the top 32 most valuable European clubs, the six Italian ones on average are worth approximately half of what the Spanish clubs are and only a third of that of the EPL clubs. In addition, the market is big: the Italian population is quite huge, with over 60 million people.

However, out of the 20 top division clubs only five are in foreign hands at the moment, while many clubs are owned by local football-loving families. As how family businesses often go, professional management competencies may come only second to emotions, traditions and commitment at some smaller clubs — an area where potential investors can see great room for improvement and revenue and profit generation.

Roma became the first major Italian team to have foreign ownership after a consortium led by Italian-American Thomas Di Benedetto bought a 67% controlling share of the club for EUR 70M in 2011 from the local Sensi family. According to media reports, the club is once again set to change owners soon: American businessman Dan Friedkin is to buy the club for a reported fee in the range of EUR 780M. Bologna was a real bargain when Italian-American businessmen Joey Saputo and Joe Tacopina bought the club for only EUR 7M in 2014. By comparison, a most recent deal was much more costly: Italy-born American magnate Rocco Commisso paid EUR 165M for Fiorentina last year, to local owners the Della Valle family. In addition to that, the two Milanese giants both saw more turbulent years in changing ownership: a majority stake of Inter Milan is now in the hands of Chinese conglomerate Suning Group, which bought 68.55% of the club for EUR 270M in 2016, while as for AC Milan, after an unsuccessful 2-year Chinese ownership spell, in 2018 American investment fund Elliott Capital took control of the club as an execution of the guarantee on the debt not paid back by the previous owners.

Looking at the main revenue streams, it is interesting to survey how these five clubs were able to manage their commercial revenues in the past five seasons. Bologna, Inter and Roma could register spectacular growth recently, while Fiorentina would hope to stabilize the evolution after last year’s Commisso deal — all could be inspirational to future investors. AC Milan‘s poor performance is a reflection of their struggles on the field. In late 2018, the club hired CEO Ivan Gazidis from Arsenal, hoping to turn the tide, especially off the pitch, but results are yet to be seen.

.png)

It is also remarkable that Italian clubs in general perform rather poorly in commercial activities. Considering the top 30 clubs from the big 5 leagues ranked by commercial revenues, Serie A clubs had the lowest average commercial income—EUR 75M in 2017/18—while averages for the other big four leagues were all well above EUR 100M.

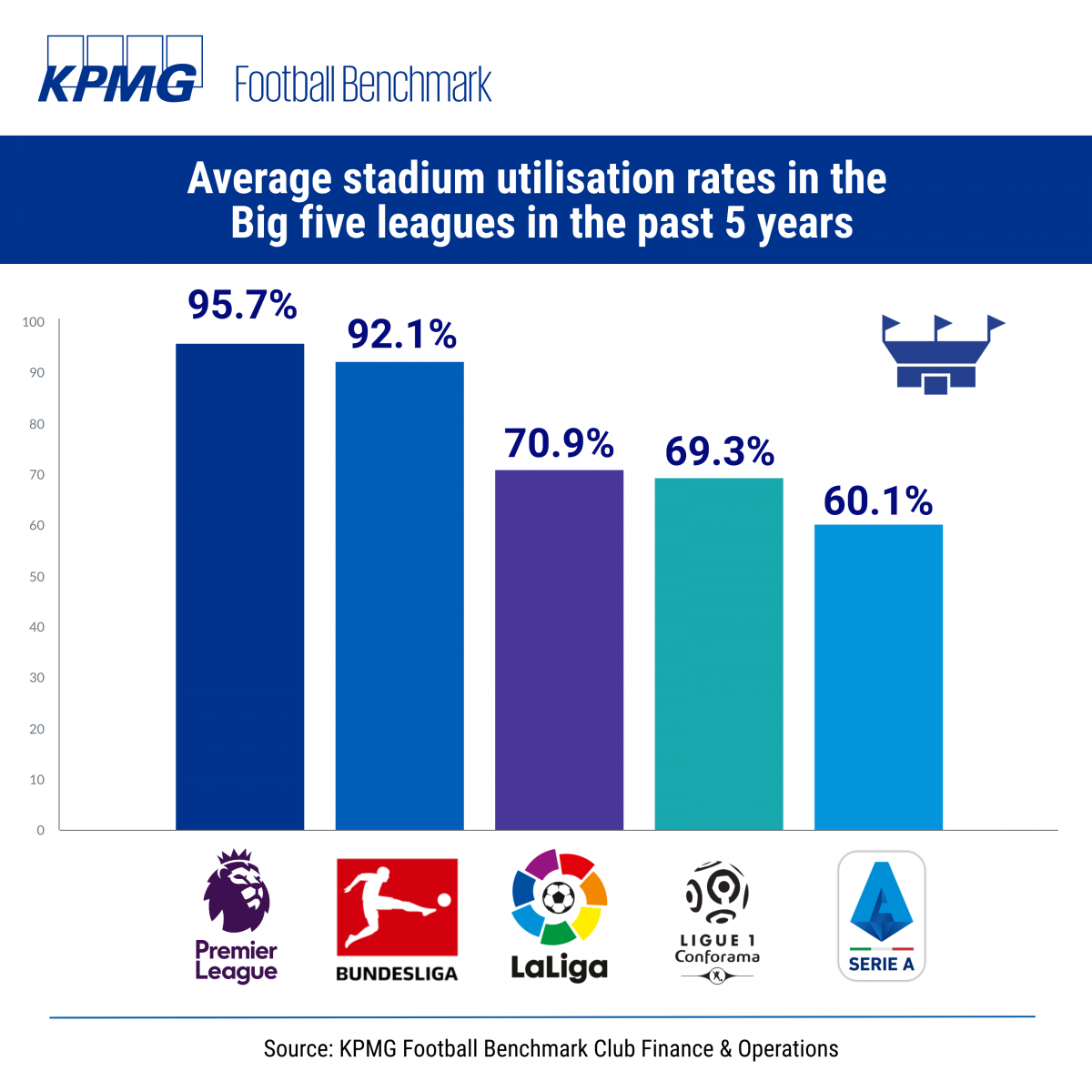

The other major revenue stream is matchday income — an area where Italy, again, presents more opportunities compared to the other big leagues. Although this revenue source is capped by ticket prices and stadium capacity, Italian stadia, in general, offer much room for improvement and revenue and profit generation for potential investors.

Italy is known for having relatively cheaper tickets and several older and bigger stadia with lower utilization figures.

It is not surprising that the new foreign owners have ambitious redevelopment plans at their clubs, hoping to boost matchday revenues. AS Roma, Fiorentina, AC Milan and Inter Milan all plan to move to newly-built stadiums. The two Milanese giants plan to jointly develop a new, 60,000-capacity stadium to be completed for the 2022/23 season, after almost 100 years at San Siro. AS Roma are set to leave Stadio Olimpico and build a new 52,000-seat stadium, but work has not started yet. A similar situation in Florence, where the new owners of Fiorentina are aiming at developing a new arena by 2023. Bologna have announced plans to reduce their stadium's capacity from 31,000 to 27,000 in a complete redevelopment of their 93-year-old stadium Dall’Ara.

Italian clubs are traditionally heavily dependent on broadcasting revenues. Currently, Serie A is in the second year of the 2018-2021 cycle. The value of domestic rights increased slightly in the current cycle by 3% compared to the previous one, from EUR 2.84 billion to 2.92 billion, while, in the meantime, revenues from international rights more than doubled.

This also leads to an argument that Italian clubs need to perform better internationally; that is, finish in a top place in the league. Serie A is fairly competitive — in the past five years only Lazio, Fiorentina and most recently Atalanta could break into the top four places, dominated by Juventus, Roma, Inter Milan and Napoli. Nevertheless, clinching a top four position, with a promise of massive UEFA money, is far from being impossible.

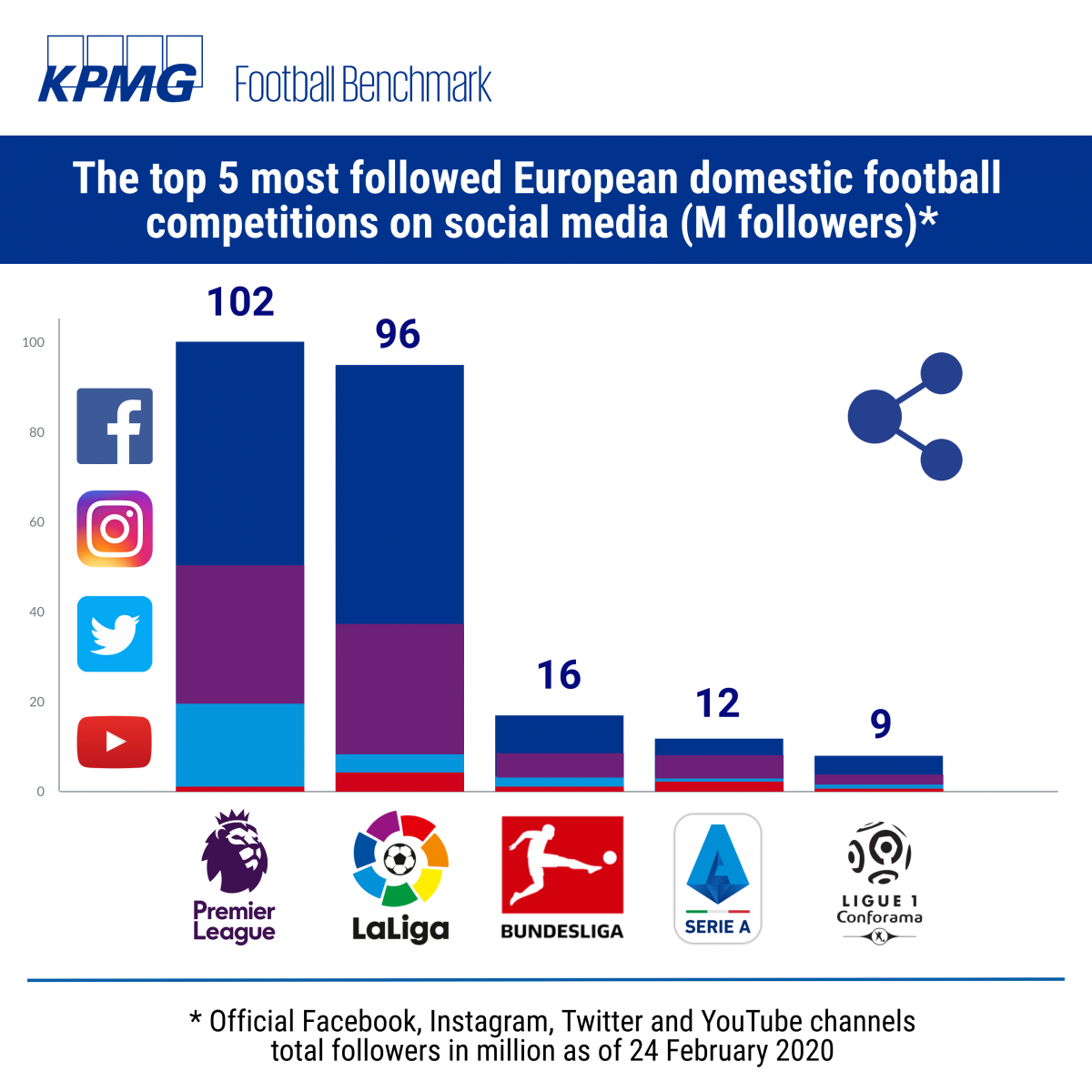

Regarding the rich history of Italian football, it may be surprising that Serie A clubs lag behind their competitors in popularity on major social media channels, yet this is another area where poorer results can be seen as a potential for growth.

All in all, underperformance in several areas both on and off the pitch in Serie A, combined with the high fame and prestige of Italian football, may provide a unique mix of opportunities for those who plan to invest in European football.

[1] All deal data mentioned in this article are from various media reports.