Over the past two years, media discussions around Chinese football have mainly focused on enormous transfer fees and, most recently, how a new regulatory framework might compromise Chinese clubs’ purchasing power. However, the development of China’s sports industry, expected to reach RMB 3 trillion (EUR 386 billion) by 2020, will require clubs not only to attract and develop talent but also to create a modern, commercially-oriented football economy.

In this article the Football Benchmark team reviews the status of Chinese Super League (CSL) clubs from a revenue-generating perspective.

The CSL’s growing stature, positively influenced by the country’s football revolution, was recently confirmed by Ping An Insurance’s renewal as league sponsor. The five-year new deal (2018-2022), worth RMB 1 billion (EUR 128 million), makes the company the CSL’s longest-running sponsor.

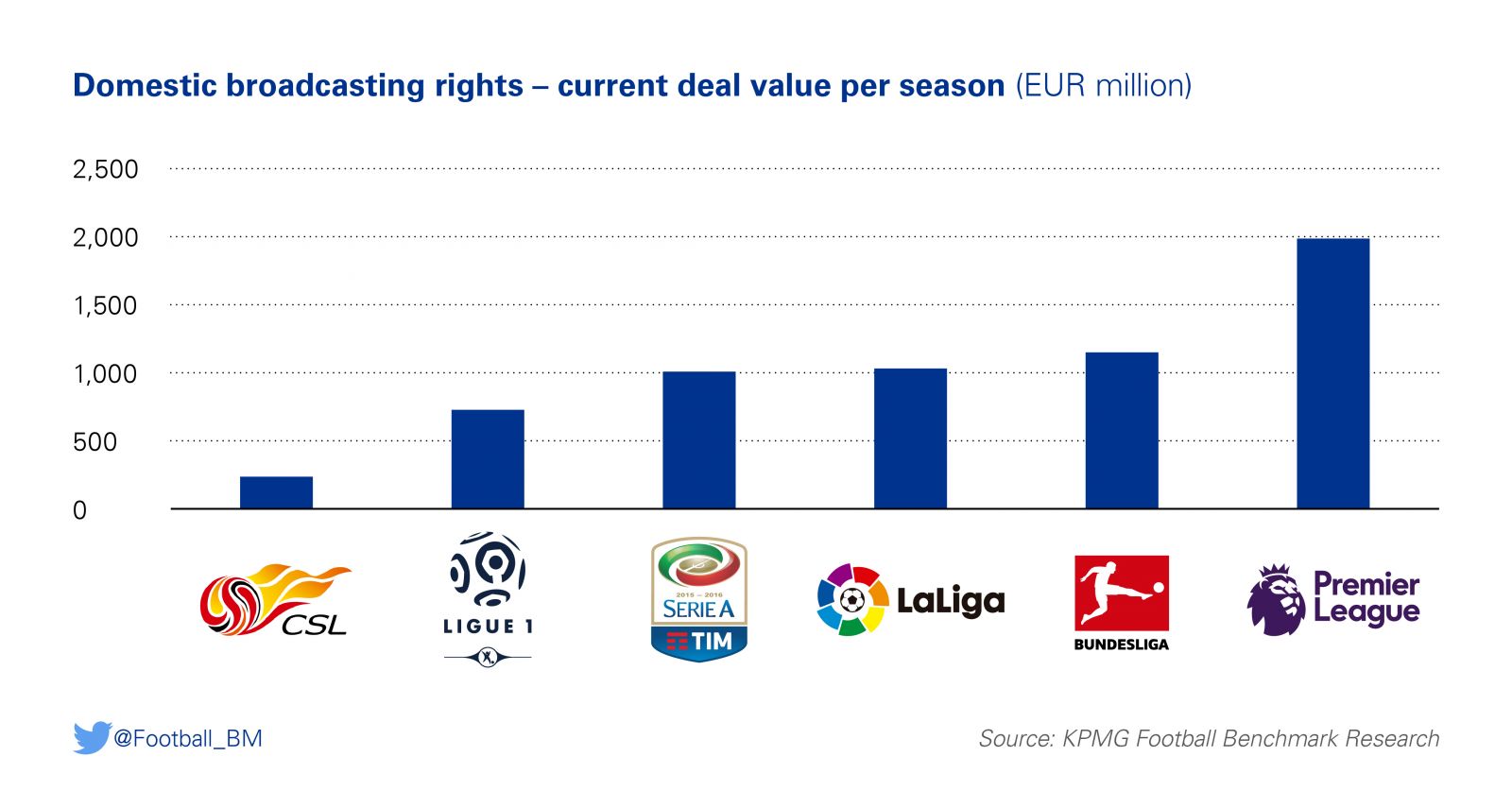

Back in 2015, the Chinese Football Association (CFA) agreement with China Media Capital (CMC) for the sale of the league’s broadcasting rights, was not only a significant increase on the previous agreement with China Central Television (reportedly RMB 80m), but also represented a definite sign of confidence in the CSL. CMC agreed to pay RMB 8 billion (above EUR 1 billion) over the 2016-2020 cycle, RMB 1 billion for each of the first two seasons of the agreement and RMB 2 billion in each of the following three.

The sudden rise in the value of rights put pressure on owners to monetize the content, including football as part of their subscription-based offering. However, CSL’s online and mobile rights, initially acquired by LeSports, were earlier this season transferred to Suning-owned PPTV, after the firm highlighted the difficulty in attracting subscribers and the challenge coming from traditional TV stations of free-to-air broadcast of CSL matches.

Moreover, earlier this month, CMC reportedly delayed its latest payment and formally requested the CFA to re-negotiate the contract, considering that new imposed regulations, aimed at controlling the investment in player signings, would diminish the media value of the product.

Despite the increase in media rights value, sponsorship still represents the main revenue source for CSL clubs. However, as with other East Asian Leagues (e.g. K.League, J.League), major assets, such as the jersey’s main sponsor, are invariably assigned to companies linked to ownership. Likewise, commercial operations are not yet comparable with other more developed football markets.

While Chinese clubs are clearly adept at exploiting naming rights, a practice more common in other sports or in smaller leagues, these assets are also commonly retained by club owners. As a result, names are often modified following ownership changes. An example can be found in the case of Alibaba’s 2014 investment in Guangzhou Evergrande, where the Chinese e-commerce giant added Taobao (Alibaba-owned online retail company) to its name and, most recently, Chongqing Lifan was renamed as Chongqing Dandai Lifan, following the acquisition of a majority stake – along with Granada CF and Parma owner Jiang Lizhang - by Dangdai International Group.

By contrast, technical sponsorship rights are managed by the CFA, a common practice in the case of emerging leagues where the negotiating power of individual clubs is still limited (e.g. Major League Soccer). In 2009 the CFA signed a 10-year exclusive deal with Nike covering all CSL clubs but in time this may be challenged as individual brands are strengthened.

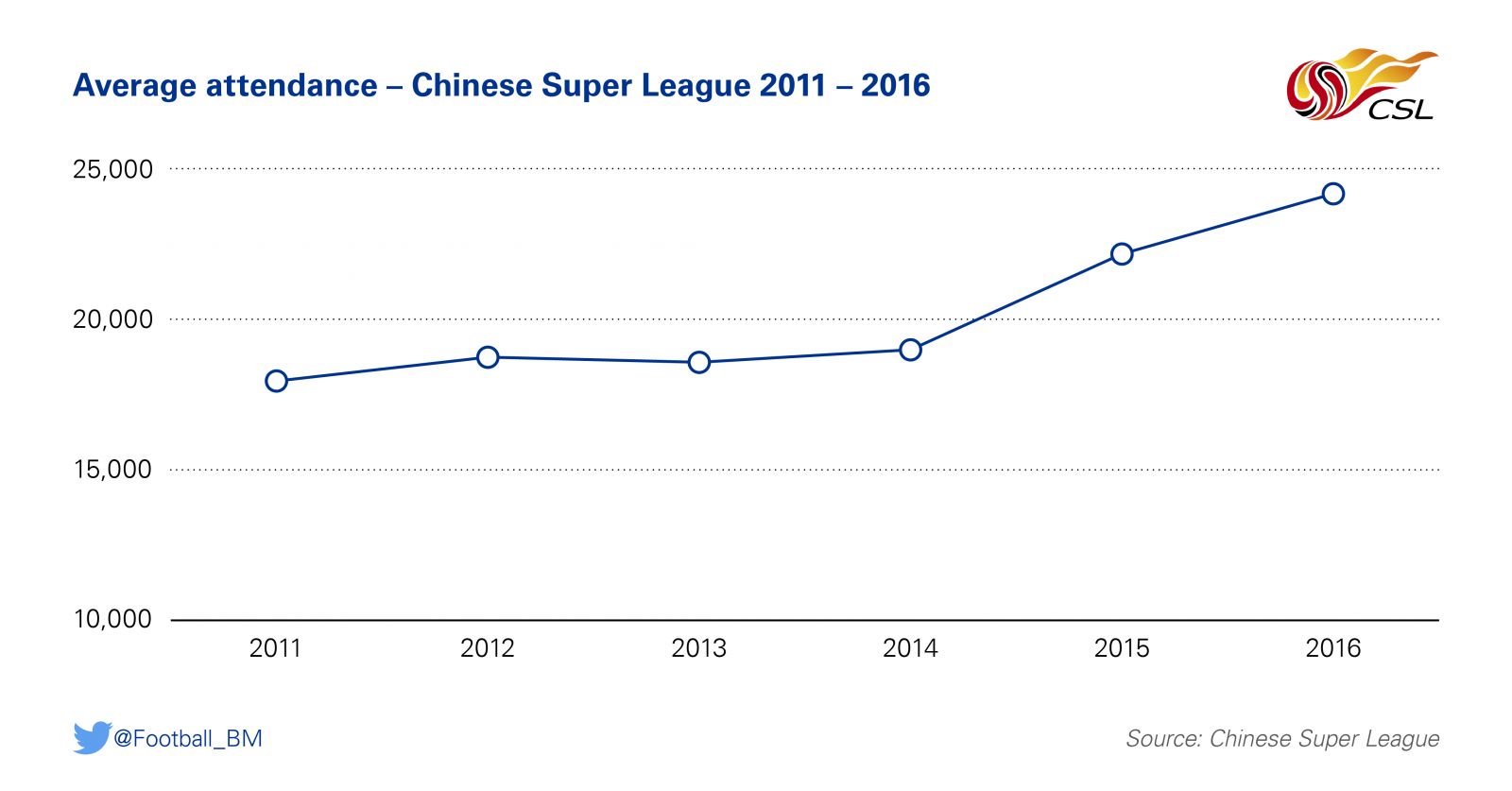

With most rights centrally-managed at league level or held by clubs’ ownership, matchday remains a key revenue stream for clubs to leverage. Indeed, stakeholders’ renewed confidence in the league has positively enhanced the position of clubs in this regard and, after a number of seasons at approximately 18,000 fans per game, a significant increase was already observed in 2015 and last season’s average crowd was above 24,000 (27% up from 2014).

However, while attendance figures are comparable to those of Spanish LaLiga, the limitation of publicly-owned, non-football-specific venues and lower ticket prices, still means that CSL clubs’ matchday revenues are considerably lower than those of their Western peers.

Moreover, attendances are, in many cases, more volatile and dependent of on-pitch success than in Europe, where loyal supporter bases have been built over many decades. For example, in 2016 Liaoning Hongyun attracted on average more than 20,000 fans to their home games, while this season the average attendance is below 12,000. Therefore, in their pursuit of offering a better matchday experience, CSL clubs are improving their home grounds, with Shanghai SIPG plans for a new football-specific venue and Guangzhou R&F’s recent RMB 60m investment in their historic Yuexiushan Stadium being a notable examples of this trend.

A review of the current landscape of the Chinese football economy demonstrates that there is room for growth across customary revenue streams. Although the overall focus is still on financial outlay in the transfer market and investment in grassroots, the development of modern organizational structures and the optimization of business operations will also be a major area of attention for CSL clubs. In an extremely competitive and increasingly regulated landscape, those excelling off the pitch will undoubtedly be in a better position to succeed on the field.

Further investigation into this and related topics, as well as analysis of industry data, can be undertaken for you by KPMG Sports Advisory Practice. Our subject matter experts can also assist stakeholders in assessing and interpreting the potential impact on their organizations of any particular piece of research, identifying the underlying reasons behind specific trends or developing potential solutions and considering future scenarios.