Porto and Ajax are the only non-big five league teams in this year’s Champions League quarter-finals – it has been 7 years since two non-big five clubs (Benfica and Apoel Nicosia) qualified for this stage. In the past 6 years, only Porto, Benfica and Galatasaray made it to the last 8. The dominance of the five major leagues was already palpable earlier in this year’s tournament, as Porto and Ajax were the only exceptions in the last 16, too.

Beating the odds this year

Ajax’s young squad already made history, when they eliminated UCL holders Real Madrid in the last 16, beating them 4-1 at the Bernabeu, overturning the 2-1 first-leg lead of the Spanish side. Against a team whose squad is worth over three times more than Ajax’s, and whose revenues are over eight times more than the overall income of the Dutch club. Ajax are running against the odds in the quarter-finals, too: the difference between the squad market values of Ajax and their current opponent, Juventus are almost EUR 500 M, while Juventus’ operating revenues are over four times more than those of Ajax.

Unsurprisingly, the situation is no different for Porto, who had the squad with the lowest market value in the last 16. In that stage, their tie with AS Roma was less unbalanced, regarding such metrics, but beating the odds in the quarter-finals seems a far tougher challenge – their current opponent Liverpool boast both squad market value and total operating revenues five times the size of Porto’s.

History repeating itself

Despite the progress Ajax and Porto are displaying this year, the Champions League has recently increasingly been dominated by clubs from the big five divisions of Europe. Interestingly, the last teams from outside these leagues that could win the competition were exactly these two clubs: Porto, who won the trophy in 2004, under Jose Mourinho, and before that, it was Ajax’s triumph in 1995 with Louis van Gaal. The last time a team from a non-big five league made it to the semi-finals was in 2005, when PSV Eindhoven were beaten by AC Milan in the semis.

In the past 10 years, 17 non-big five league teams could move on from the group stages to the last 16, while only 6 of them succeeded in progressing to the quarter-finals, too – Porto and Benfica twice each, plus Galatasaray, Apoel Nicosia, Shakhtar Donetsk and CSKA Moscow once each). This also means that in the past decade, on average, non-big five leagues provided about a fifth (21%) of the clubs in the last 16, whereas in the quarter-finals their representation was only 10%.

Ways to sustain regular participation

Some non-big five league clubs are able to maintain the potential to be regularly involved in the group stages and occasionally in the knockout phases of the Champions League. How are they able to do so?

Top clubs of the European elite benefit from the presence of star players, established market positions and secure income streams. The regular non-big five league contenders in major European tournaments are generally mid-size clubs operating in smaller markets, with a limited number of star players and established positions in their domestic leagues. They can generate significantly less overall revenues than the top, big-five elite clubs, and cannot build similarly stable, top-value squads either.

For them, the key to secure regular entry into European competitions is to ensure that they can maximize their squad value within their financial capabilities. One pillar of achieving that is quality talent management. Indeed, several clubs look at talent development as the main tool to improve their chances of success. Clubs like Porto, Benfica and Ajax are famous for their academy infrastructure, producing home-grown talents and also scouting primarily local talents from their domestic leagues, who then can make strong, competitive squads even on an international level. A parallel mechanism, more characteristic to some Turkish, Russian and Eastern European teams, is to acquire talents and less expensive, experienced quality players from the international markets.

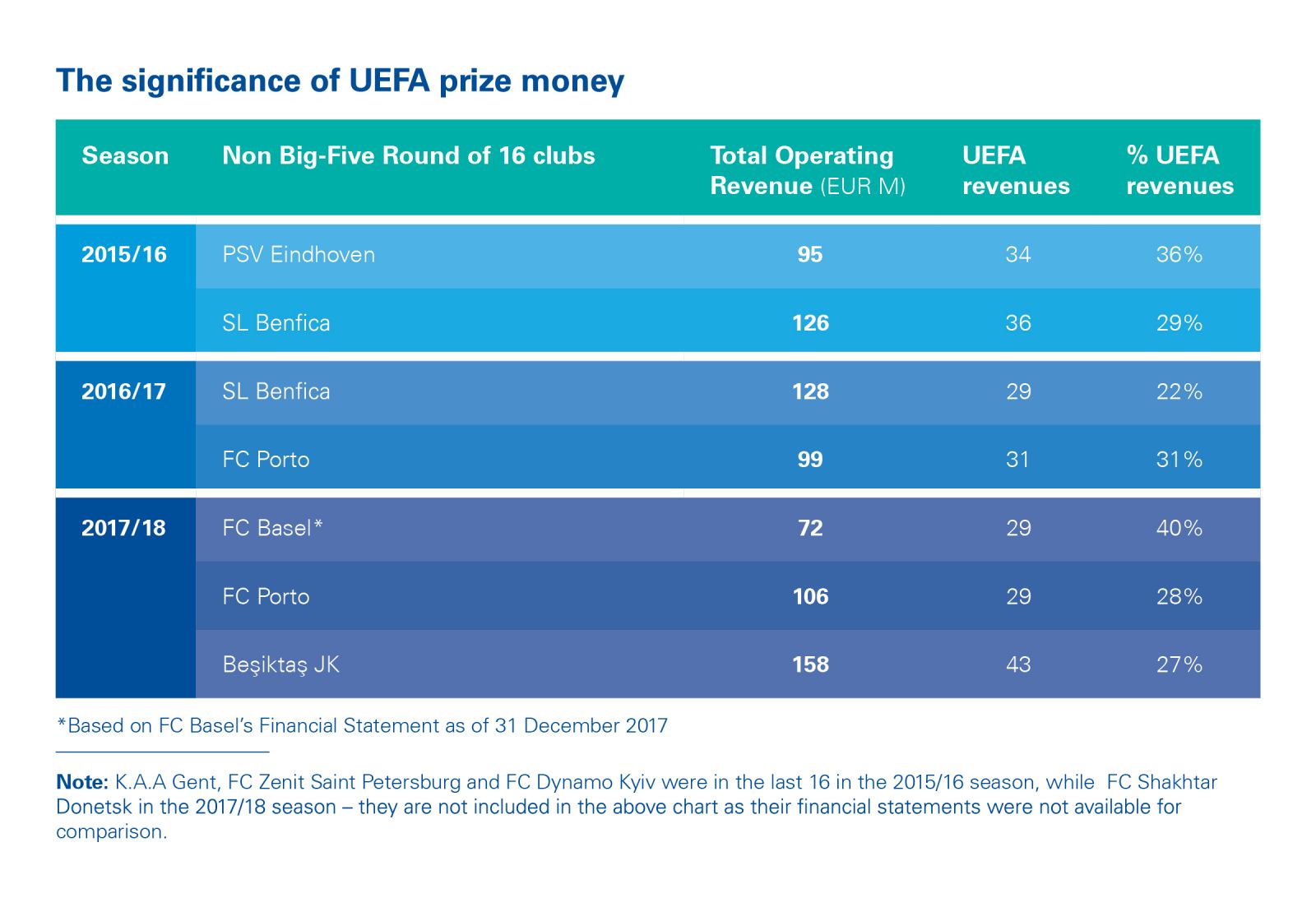

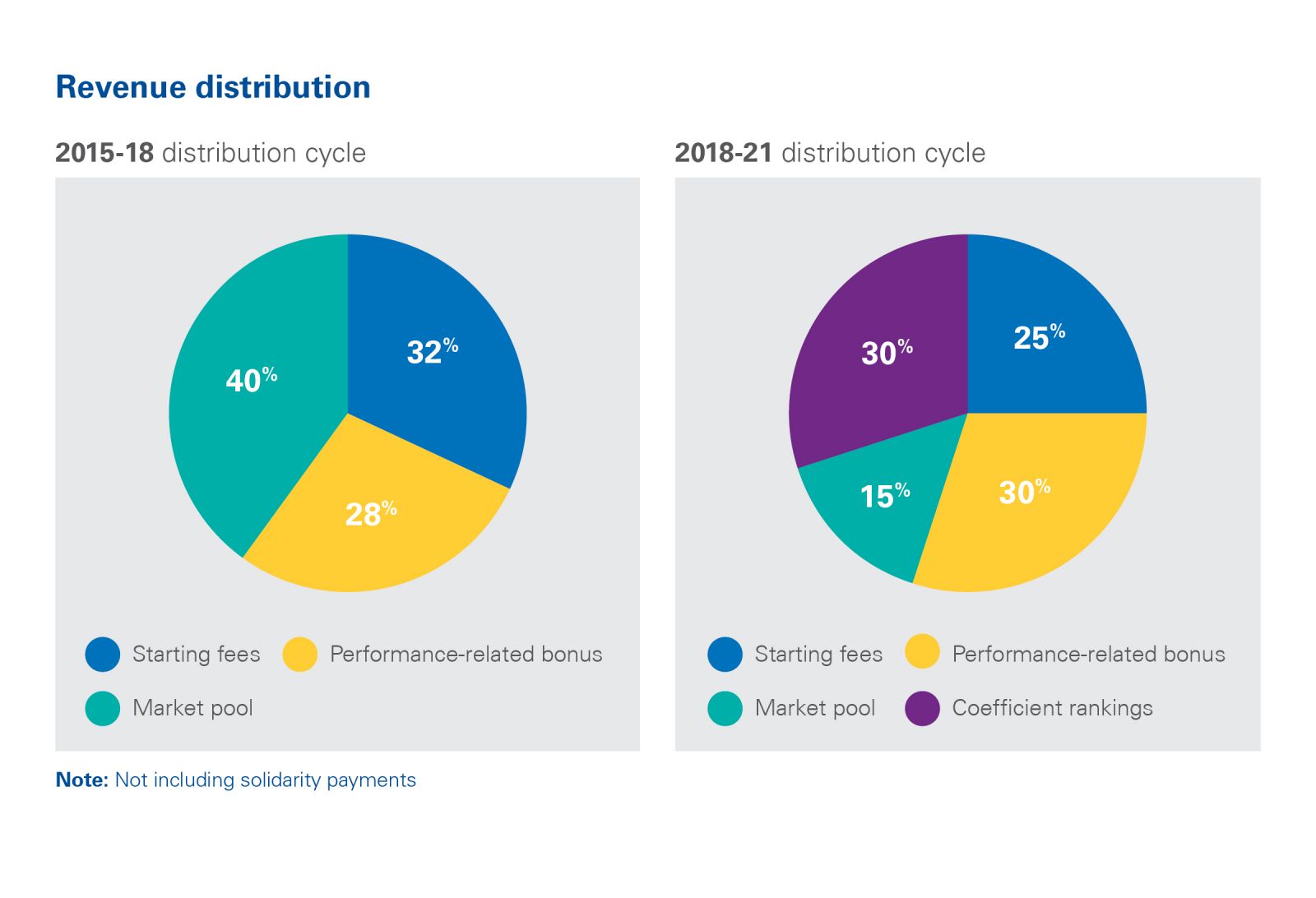

The other pillar is the virtuous cycle of participating in the Champions League: the UEFA prize money distributed to teams who make the UCL, along with increased matchday and broadcasting revenues, can add significant volumes to the overall income of these clubs. With the extra revenues acquired from Champions League football, they can invest in better players than their domestic rivals, and thus repeatedly can finish on top of their local championships, which again guarantees participation in international competitions. Indeed, the revenue non-big five league clubs may cash in from UEFA prize money is often a very significant bulk of their total income. Our chart below shows the proportion of this income in the case of the last 16 contenders from non-big five leagues in the past three years. In addition, the UEFA financial distribution system also allocates solidarity payments to the clubs who are either not participating in or are knocked out at the qualifying phase, mostly non-big five clubs.

The new, 3-year (2018-2021) UEFA club competition cycle has introduced some changes in the UCL, aimed at distributing revenues more evenly and thus improving competitive balance. Overall financial contributions will be increased significantly to clubs, while the 4-pillar, new financial distribution system (starting fee, performance in the competition, individual club coefficient and market pool) will see the market pool share decreased.

However, as the new “club coefficient” item is largely calculated on a club’s historical achievements, elite clubs will benefit more. Also, a bigger distribution budget means that the top teams will cash in more again, especially as they are more likely to progress to the last stages. In addition, the UCL access list to the group stages (32 teams) seems to cement the dominance of the big five championships. They can now send 18 clubs directly to the group phase, compared to the 13 clubs in the former system. The elite of the non-big five leagues can send further 6 clubs directly (two teams from Russia, plus Portugal, Belgium Ukraine and Turkey can send their champions) to the group stage. As two direct contenders are the winners of the UCL and the Europa League of the previous season, only the remaining six spots are to be decided through the qualification phase.

Whether these changes will indeed help improving competitive balance for the benefit of clubs and leagues outside the big five championships, is a question. It also remains to be seen, if anything will materialize from the rumored changes being planned to the European club competition system.

Crystallizing powers and growing predictability

Until then, most non-big five contenders in the European leagues need to face the fact, that they may be giants at home, but only small fish in Europe. For clubs from smaller markets – similarly to mid-size clubs from the Big 5 – the greatest challenge lies in retaining their best players, who understandably want to move to one of the top leagues and clubs to boost their careers. Nurturing talents and soon losing them has become a recurring pattern for these clubs. Therefore, long term planning that enables them to constantly reframe the squad is vital.

“While Ajax and Porto may break the overall trend this season, recent years show that financial power is increasingly concentrated in the elite big five leagues, enabling them to form exceptional squads, which, in turn, can attract more revenues – and the cycle is set. Smaller leagues and clubs have their chances, yet, as recent developments show, international success for them looks increasingly like a rare miracle. With great organizational skills on pitch, exceptional performance and some luck, they may work wonders once in a while, but more and more rarely.

When they do, we love football even more,” Andrea Sartori, head of the KPMG Football Benchmark team commented.