As the group stages of this year’s UEFA Champions League draws to a close, KPMG Football Benchmark Team has looked at the evolution of the UEFA Champions League (“UCL”) in terms of the various nations represented in what is the pinnacle event of European club football.

Since it replaced the European Cup in 1992, the UCL has experienced several major changes, both to the way it works and in the tournament’s schedule. Before 1997, only the actual champions of the top domestic leagues qualified for the UCL i.e. each year approximately three fourth of the participants who made it into the group stages were from the non-‘big five’ leagues as we know them today, namely the English Premier League, Spanish La Liga, German Bundesliga, Italian Serie A and French Ligue 1. In 1997 the number of teams in the first round was expanded to 24, allowing participation to more than one team per country for the first time[1]. Two years later, in 1999, the Champions League was expanded to the current format of 32 teams.

Since the 2000/01 season, the ‘big five’ leagues have provided approximately 50% of the clubs which have made it into the group stages. The switch to a new format was agreed after lobbying by some larger and more powerful European clubs who, despite not being national champions, did not want to miss out on the opportunity to take part in arguably club football’s most prestigious and financially rewarding competition.

The new composition of the tournament allowed a number of large and highly recognised clubs to play on the European stage. The new structure of the competition resulted in increased popular awareness of the tournament and growing exposure to a global audience. However, it could be argued that with such a competition format the overall competitive balance of the UCL has been affected.

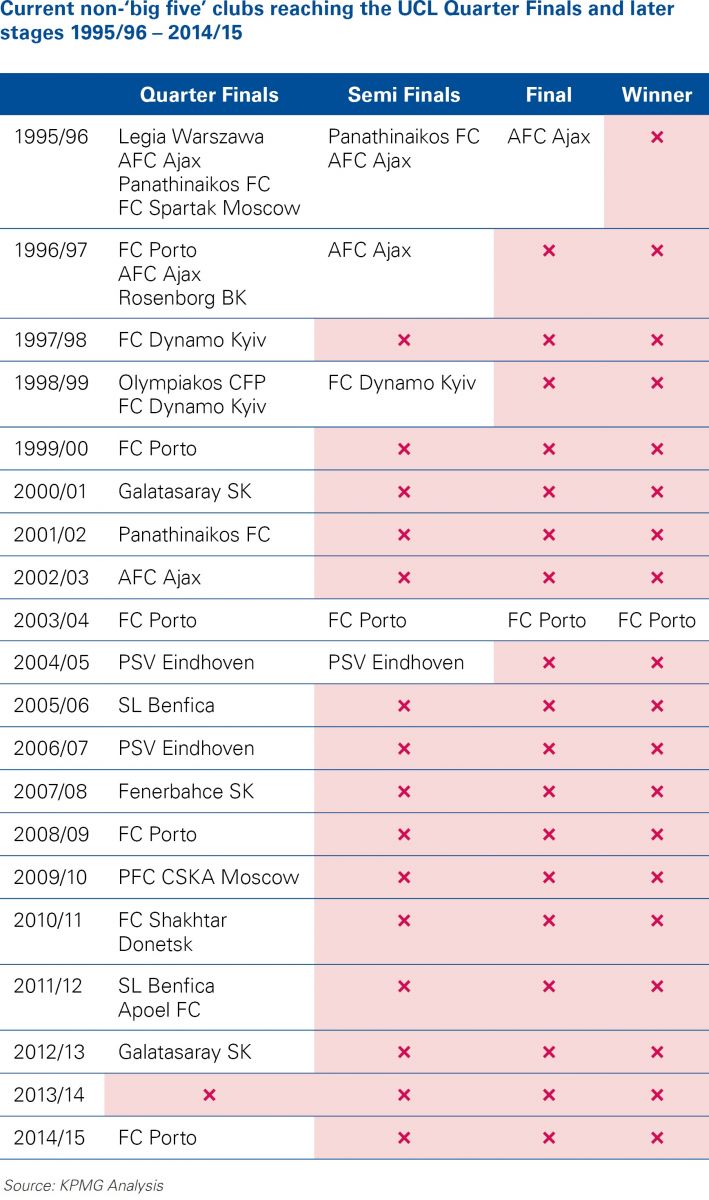

In fact, as it is shown in the table below, over the last decade (2005/06-2014/15) clubs from outside the ‘big five’ leagues made it to the quarter-finals of the UCL only ten times, and none of these advanced through to the semi-finals. This compares to the previous decade (1995/96-2004/05) when 16 times clubs from outside the ‘big five’ leagues reached the quarter-finals, six times advancing to the semi-finals, and twice to the final itself, resulting in one eventual winner (Porto in 2004).

Going further back in time, in the second half of the 1980s and in the early 1990s four clubs from outside the current ‘big five’ won what was then the European Cup - FC Steaua Bucharest in 1986, FC Porto in 1987, PSV Eindhoven in 1988 and FK Red Star Belgrade in 1991.

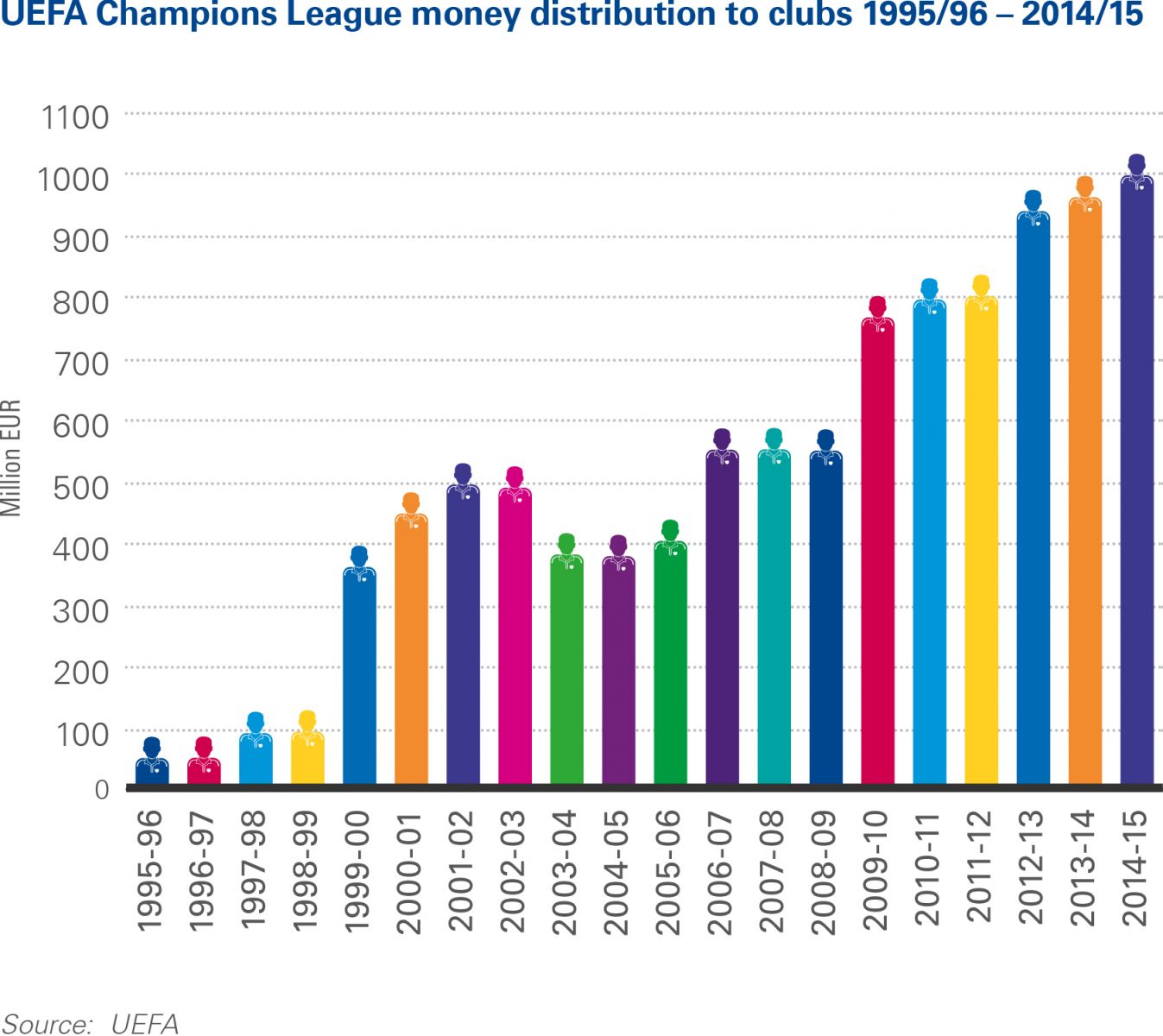

Since the number of clubs from the ‘big five’ leagues taking part in the UCL grew after the increase in the number of teams, these big league clubs have been able to enjoy most of the revenues distributed by UEFA. As an example, in the 2014/15 season the semi-finalists (Juventus FC, Real Madrid FC, FC Barcelona and FC Bayern Munich), all coming from the ‘big five’ leagues, accounted for 25% of the total revenue distribution, and in the decade up to 2015, just ten teams have shared around 50% of the total prize and broadcasting money distributed by UEFA. These figures exclude UCL matchday income from playing UCL matches, sponsorship and other revenues that arise because of participation in the tournament.

As for broadcasting and prize money, UEFA distributed in excess of EUR 10.8 billion in the two decades under consideration here.

It is evident that the competition structure and UEFA’s revenue distribution system, combined with other factors we consider below, have contributed in the last decade to an imbalance of power in favour of a limited number of clubs belonging to the ‘big five’ leagues, predominantly Spanish, German and English clubs. Unsurprisingly, the ‘big five’ leagues are played in the most economically powerful and populated countries in Europe. Clubs in those countries have large fan bases and their domestic league broadcasting rights can be sold at significantly higher levels than those of other European countries. These economic circumstances give the most prominent clubs in those leagues the opportunity to generate comparatively higher revenues, which in turn allows them to invest and attract the best players on the market. By signing better players, clubs are then able to enhance their sporting performance, leading to improved UEFA nation coefficients, maintaining the superior number of places available to the top countries to take part in the competition[1], and hence a vicious circle perpetuates itself.

Nevertheless, the 2015/16 season will be the first to see a new cycle of revenue distribution which will run between 2015 and 2018; the amount awardable to all participating clubs will rise to almost EUR 1.3 billion per season, a 26% increase compared to the 2012-2015 cycle. Not only will the competition become more lucrative to clubs, but also the mechanism of revenue distribution will change. The influence of the market pool – the value of each broadcasting market represented by participating clubs – has been reduced from 45% to 40%, and the fixed amounts – prize money based on on-pitch performance – have increased to 60%. Furthermore, 10% of the respective associations’ market pool share will be allocated to clubs eliminated in the play-offs, an arrangement that was not present in previous cycles.

In order to promote competitive balance, UEFA also makes solidarity payments to clubs who fail to qualify for the group stages and to those not qualified to UEFA competitions at all. In the first case, the distribution pot will increase by 60% to EUR 78.6 million, while in the second case by more than 35% to EUR 112 million.

Whether or not the impact of these changes on the overall revenue distribution will have an impact on the progress of clubs outside of the ‘big five’ leagues may take some time to assess. However, with the size of the pot growing larger, it is inevitable that the bigger clubs will still benefit more than others, suggesting that we may not see the likes of Porto’s triumph in 2004 for some time yet. With 90 minutes still to be played in this year’s UEFA Champions League group stages, two non ‘big five’ clubs have already qualified for the round of last 16 (SL Benfica and FC Zenit Saint Petersburg), while another six still have a shot at making it to the next round.

KPMG’s Football Benchmark Team can undertake further analysis of football industry data for you. The subject matter experts within the group can also assist stakeholders to assess and interpret the potential impact on their organisations suggested by the results of particular pieces of research and to identify reasons why a specific trend is being observed or to assess potential solutions and future scenarios.

[1] For the 1992/93 and 1993/94 seasons, only eight teams took part in the UEFA Champions League; from 1994/95 to 1996/97 (three seasons), 16 teams participated in the competition.

[2] As of today, Spain, Germany and England have four slots each, while Italy and France have three each. The maximum number of places is four.