European football produced the most thrilling action this week – not in the form of fantastic on-pitch performances, but in a 48-hour war, a colossal power gamble, in which the continent’s breakaway leading clubs finally surrendered. While the fierce battle seems to be over, there is no reason to triumph as true peace is still far away. Also, while the renegade 12 elite European clubs shall go on with their own particular business considerations, the core problems that led to this turmoil remain unsolved and to be addressed.

Therefore, after a brief recap of the main drivers of such turmoil, we aim to focus on the future – what is next, what are the key areas decision makers should focus on to move forward towards a more sustainable European football industry.

What led to the revolution of 12 of Europe’s most powerful clubs?

- Increasing crystallisation of sporting results and polarisation of clubs’ economic power.

- Media landscape evolution: through the appearance and growth of social media and streaming platforms in recent years, football has become accessible at relatively low cost anywhere in the world at any time.

- This transformation had two effects: firstly, it changed the way fans (especially generation-Z, expecting top-end digital entertainment and communication solutions) access and consume football and, secondly, it transformed large football clubs - who have become media and entertainment enterprises, rather than sporting organizations - into true global brands, generating the majority of their revenue from commercial activities.

- Huge economic losses and high amounts of debt, which have been further magnified by the coronavirus pandemic. The entrenched and long-lasting impact of the COVID-19 crisis has accelerated the needs of structural changes to the football eco-system in order to ensure the game’s long-term financial health.

- Even pre pandemic, need to stabilize cash-flows and reduce the financial implications associated with sporting performance risk.

- Limited control on the governance of international clubs’ competitions and revenue distribution vs. entrepreneurial risk, almost entirely borne by the clubs.

- Perceived missed maximization of UCL income, mainly due to its format, compared for example to the American leagues.

The below chart shows the global social media popularity of the original 12 ESL rebel clubs, compared to all the other clubs in the big five leagues.

.png)

What to do next?

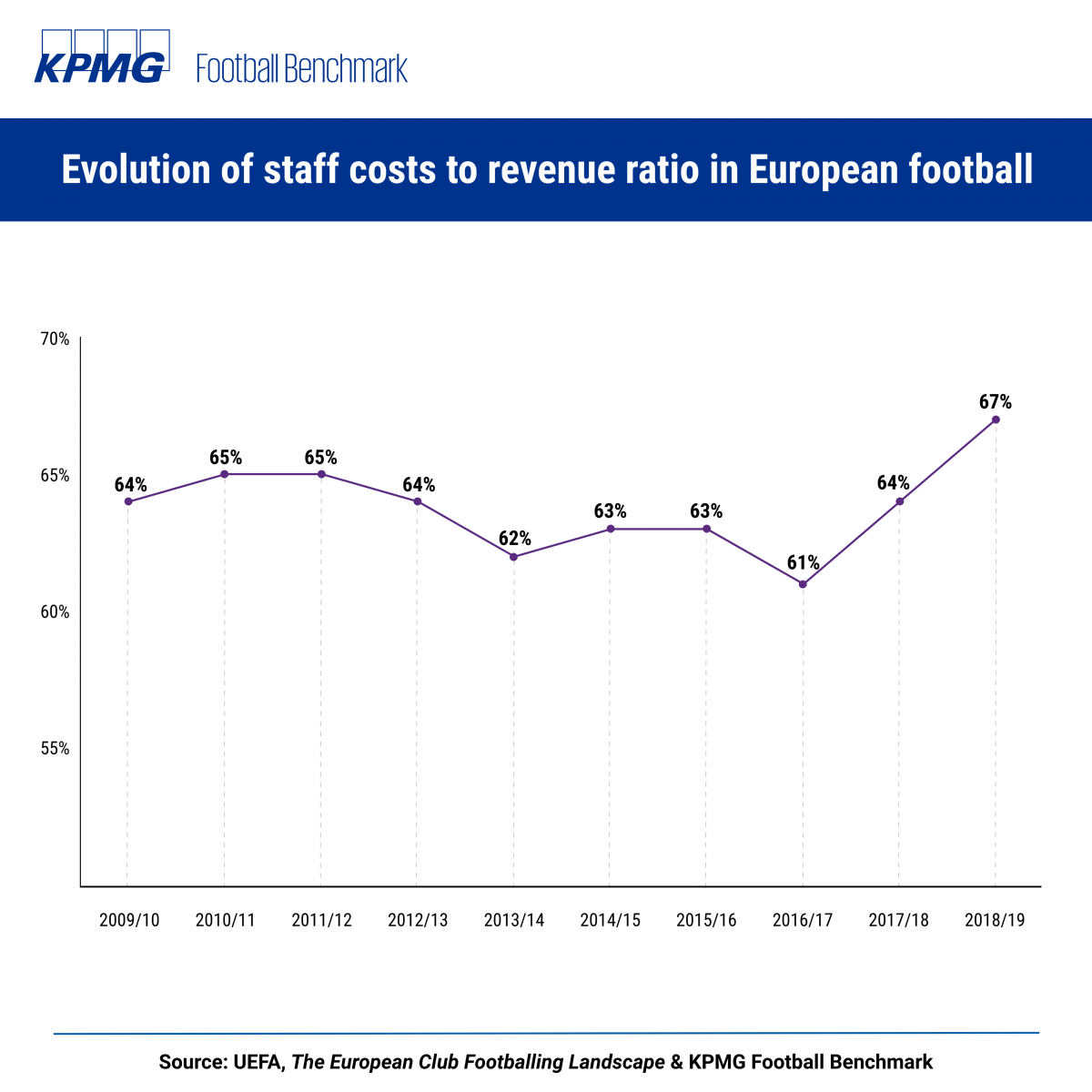

Reform of the Financial Fair Play regulation system

More consistent and rigorous cost control is essential to improve sustainability, as many clubs’ revenues are absorbed by their ever-growing staff expenditures as demonstrated in the chart below, showing the staff cost to revenue ratio evolution of European clubs. A more stringent system is required – with the break-even requirement redesigned, the focus broadened to all the financial commitments of clubs and primarily, with improved cost control mechanisms. The introduction of a soft salary cap, although complex because of EU competition law, deserves serious consideration. In this regard, it is relevant to highlight that the rigid nature of the cost structure of football clubs, strictly linked to the long-term player contracts, will require time for salary cap measure, which will have to be gradually introduced, to become fully effective.

Another area of intervention, which can assist in ensuring better cost control, is a transfer system reform, with a particular focus on transfer and agents' fees.

Reform of match calendars

There is a need for rationalization and better coordination of the domestic and international match calendars in order to have as many meaningful matches as possible both at national and international level. The reduction of the number of clubs in some leagues (e.g. from 20 to 18 in four of the Big-5 leagues) could open space for additional international club tournament matches.

Consideration should also be given to the number of matches played by footballers also playing for their national teams, to ensure they are receiving the necessary resting periods during the year and recovering time between matches. Both of which are key requirements to protect the players’ health and promote enhanced performance, as addressed by FIFPRO, the representative organisation for professional footballers.

Reform of governance

There is a need for change in football governance and in the redistribution of decisional powers. As said, top clubs bear the financial risk of their operation and investments but may have relatively limited say on the distribution of their revenues.

That was the fundamental issue with the ESL-12 clubs – while they generate the majority of revenues and also invest the most, they felt their power in the decisions regarding the dispersal of those revenues was unproportionate, both on the domestic and international scenes. In particular, they felt their word in urging reforms regarding the Champions League was not treated on merit, claiming that the UCL did not offer enough high-quality games and did not capitalize on the broadcasting revenue potential.

Also, and similarly important, governance reforms should include efficient measures to enhance the sustainability of the whole football pyramid, through improved solidarity payment mechanisms.

Reform of smaller markets – regionalization

Decision-makers in the football industry should target improving the competitive power of less developed football markets.

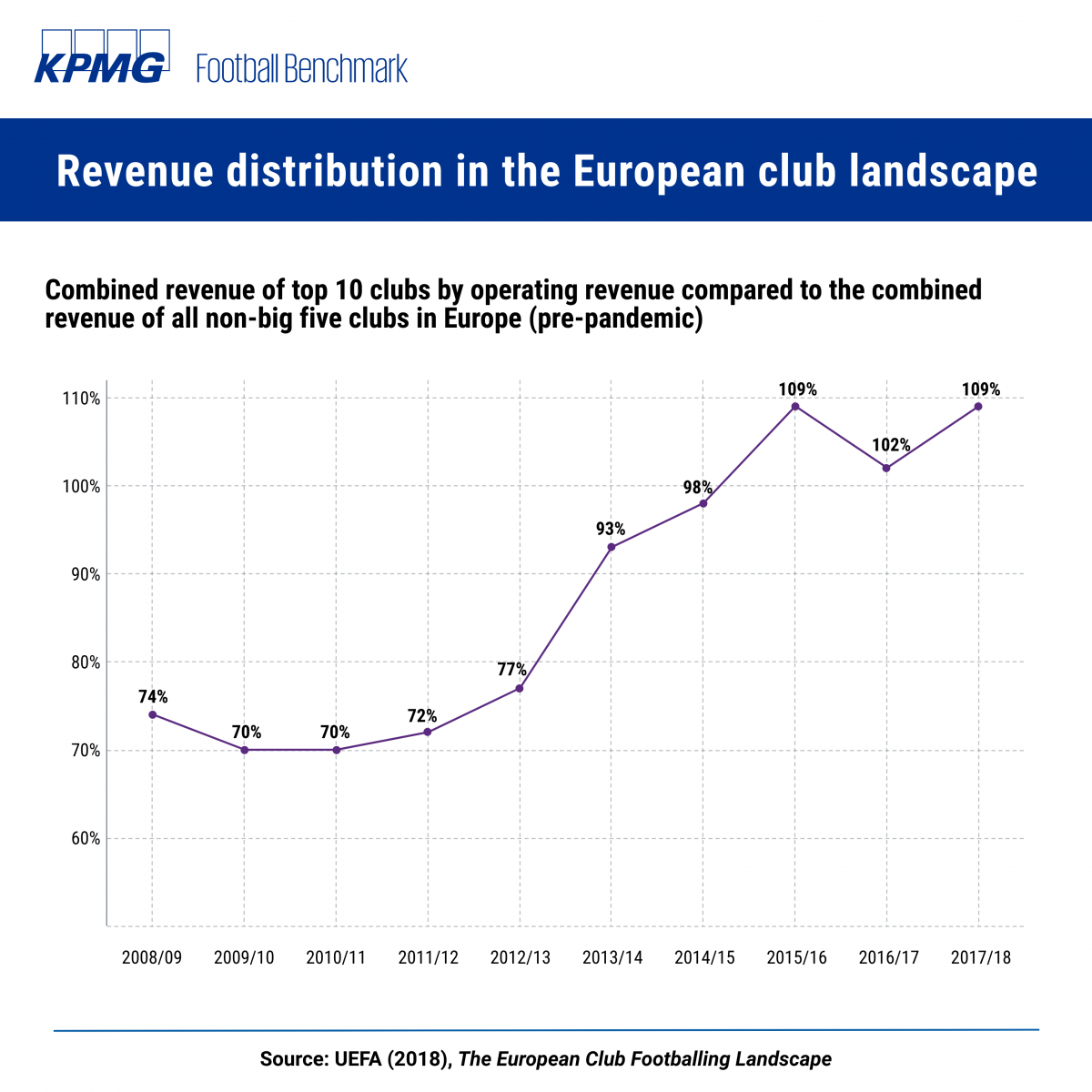

As the chart below shows, since the 2015/16 season, the top 10 clubs by operating revenues generated higher income in every year than all the non-big five European first division leagues combined (approximately 600 clubs). In the last 20-years, only three clubs (out of 80) playing outside of the Big-5 leagues, reached the semifinal of the UCL, with only one of those winning it in 2004: FC Porto.

Creating regional leagues by merging smaller domestic ones could lead to a power-consolidation in sizable markets – e.g. the planned BeneLiga, involving top Belgian and Dutch clubs, bear a potential to become the 6th biggest league in Europe. Similar merges could be worked out, for example, in Scandinavia, the Balkans or in Central and Eastern Europe. Such regional leagues would develop markets with critical mass of fans and improved football product, offering a more appealing proposition for commercial and broadcasting partners. Regional leagues would therefore become more competitive on the continental scene, provide a clearer pathway for clubs to qualify for the top competitions such as the UCL and help develop a more balanced European football landscape.

These recommendations do not purport to be exhaustive, as more considerations are deemed necessary in order to tangibly reform European football and meet the various parties’ distinctive interests and expectations, but this could be considered as the starting point before broadening the discussion.

This week’s havoc proved that reform endeavors in the recent past were insufficient. It has also caused tremendous damage in trust. Nevertheless, football’s governing bodies, associations and clubs now have to rebuild trust and start negotiate vital reforms. Unprecedented flexibility, wisdom, responsibility and cooperation from all parties at all levels is needed. There is no other way.